Table of Contents

The ancient chiefdom of Rapa Nui, Easter Island as imagined by ChatGPT 4o

Introduction

Easter Island aka Rapa Nui aka Isla de Pascua. Another bucket list item for myself. I don’t know about you all, but when I think of Easter Island, I immediately imagine those giant stone heads, you know the ones I’m talking about. The ones that have their own emoji: 🗿

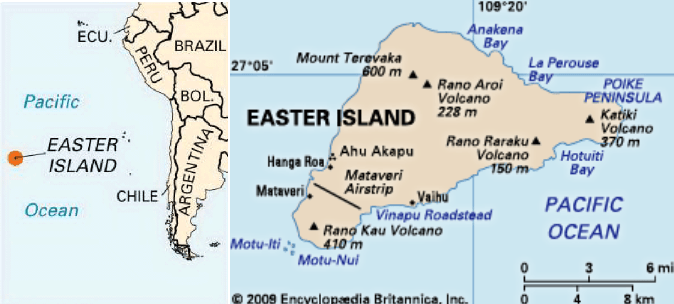

Easter Island was originally settled around 1200 CE by Polynesian navigators, located deep within the south-eastern Pacific Ocean, around 3,500 kilometres/2,175 miles west of Chile’s coast. The island itself covers an area of around 163.6 square kilometres or 63.1 square miles with a known population of about 7,750 people (as of 2017). It was an island that was covered with dense forests, including the now-extinct Easter Island palm but now is mostly grassland with few trees primarily due to historical deforestation.

The name “Easter Island” comes from its European discovery by a Dutch Explorer named Jacob Roggeveen on Easter Sunday of 1722. But it’s indigenous name, Rapa Nui, means “Great Rapa,” Rapa being the name for the island and Nui meaning great. But as I mentioned above, Rapa Nui is probably best known for tehri Moai statues, of which there are nearly 900 in total - all unique to Easter Island and iconic symbols of their culture.

But perhaps a lesser known mystery around Rapa Nui is it’s Rongorongo script, an undeciphered system of glyphs that were discovered on wooden tablets (and other artifacts), presumedly carved with some sort of sharp object. The Rongorongo script is unique and significant because it represents one of very few indigenous scripts in Oceania.

Easter Island continues to exist as a special territory of Chile, after being annexed in 1888, but still operates as part of Chile’s Valparaiso Region, with a degree of administrative autonomy. And while the traditional language is known as Rapa Nui, a Polynesian language, Spanish is widely spoken throughout the island today.

Strategic Traits of Rapa Nui

1 — Geographical Territory

Rapa Nui is one of the most isolated inhabited islands in the world, with a compact and manageable territory. This isolation provided a natural defence against outside threats, enabling the Rapa Nui people to develop a distinct and self sustaining micro empire.

The island is of volcanic origin, within three main extinct volcanoes: Terevaka, Poike and Rano Kau all contributing to Rapa Nui’s rugged and unique landscape that provided natural fortification, influencing their settlement patterns and defensive strategies.

The Rapa Nui people strategically placed their settlements in locations that leveraged the island’s natural defenses. Villages were often positioned near the volcanic slopes that provided natural protection from coastal attacks. The clustering of their homes and communal structures near these natural fortifications also meant that the need for any extensive man-man defensive works were greatly reduced.

The volcanoes provided much needed high grounds with strategic vantage points to monitor for potential threats as well as a natural barrier against invaders. Rano Kau specifically acted as a natural fortress that was very difficult to assault, offering protection for the inhabitants who could retreat to this area in times of conflict. The island’s volcanic activity also meant that there were numerous caves and underground tunnels that were also utilized as hiding places and shelters, with some caves modified and expanded to serve as secure storage areas for food and supplies in the event of a siege.

The Rapa Nui society was divided into various clans or tribes with internal conflicts between these groups often developing. Competition for limited resources such as land, fresh water and food was usually the causes for skirmishes and warfare among the clans.

I can’t in good faith talk about Rapa Nui’s geographical territory without mentioning the Moai statues and their purpose beyond cultural and religious significance. These imposing figures were often places on ahu platforms facing inland and it is speculated that their positioning could also intimidate potential invaders and symbolize the strength and unity of the Rapa Nui people.

2 — Population & Economic Scale

Think small. Rapa Nui’s population is believed to have peaked at around 10,000 individuals before their decline. The society was organized into various clans or tribes known as Mata, each with their own territory and leadership. These clans were responsible for constructing the moai statues 🗿 as well as managing their own resources as part of a decentralized but interconnected societal framework.

With their small size, they were able to centralize their governance with easier control over resources, contributing to the cohesion and stability of ancient Rapa Nui society. The island was divided into distinct territories controlled by each clan. These areas were outlined by natural landmarks and sometimes by the moai statues.

Each clan was led by a chief, known as an ariki, who held both a political and religious authority over the clan. The Ariki was often believed to have a divine connection with their responsibilities extending to leading ceremonies for their people, managing resources and making decisions that affected the welfare of their clan. The Mata hierarchy also included positions of sub-chiefs and other important figures who helped in governance and administration.

The Rapa Nui economy was driven largely by agriculture and fishing. They cultivated crops such as sweet potatoes, taro and yams in manavai (stone-walled gardens inspired by the craters of volcanoes like Rano Kau) and relied heavily on fishing and bird hunting for protein.

Perhaps in spite of their natural resources, the Rapa Nui people developed innovative agricultural techniques, like the manavai I mentioned above to protect their crops and enhance soil fertility. They also practiced sophisticated resource management strategies, such as the construction of large water reservoirs and soil conservation measures, which were crucial for sustaining their population and maintaining the economic scale of their micro empire.

3 — Influence & Autonomy

I’ve said once and I’ll say it again (probably for the 5th time in this newsletter): Moai statues. The construction of the moai statues and the ahu platforms they’re based upon are single-handedly the most significant cultural and religious influence from the Rapa Nui. The moai statues represent deified ancestors and were central to Rapa Nui’s spiritual and social life as well as being amazing examples of advanced engineering and communal organization.

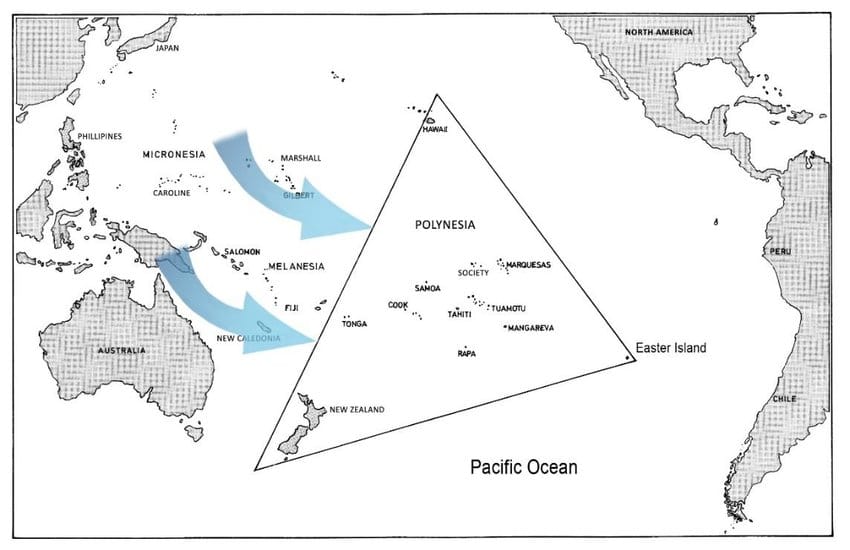

In saying that, being that the Rapa Nui people were part of the larger Polynesian cultural sphere, they also excelled at navigational and maritime skills. Despite their isolation, their ability to travel and communicate with other Polynesian islands also bore significant influence within the region. Some of the Polynesians who eventually settled on Rapa Nui are believed to hail from the Marquesas Islands with archaeological and linguistic evidence identifying a number of key similarities.

Despite the lack of solid evidence to confirm the evidence of direct communication between Rapa Nui and other islands, due to the shared cultural traits between a number of Polynesian societies including: language, religious practices and social organization its hard to dispute the possibility of a broader network of cultural exchange and influence within Polynesia.

Rapa Nui’s Clan-based governance also allowed for autonomy within the island while maintaining a cohesive society through their shared cultural and religious practices, but perhaps the best example of their autonomy comes down to their resilience and adaptation. Despite external pressures from European contact, slave raids and introduced diseases the Rapa Nui people demonstrated strength in their resilience and adaptability - holding out for as long as they could. They were able to maintain their cultural practices and societal structure in the face of these challenges for quite some time before they eventually succumbed.

4 — What happened to Rapa Nui?

Once the Europeans made contact with Rapa Nui around 1722, the island began to face a number of external threats, including slave raids and the introduction of foreign-borne diseases.

Between 1862 and 1863 Peruvian slave traders devastated the island when they raided and captured a significant portion of the population, including many leader's and knowledgeable elders. This had a catastrophic impact on Rapa Nui’s social structure and cultural knowledge - with much of the island’s traditions and practices being lost with the lives that were captured.

Eventually, Rapa Nui also suffered ecological collapse with rampant deforestation, soil erosion and the overuse of resources leading to the breakdown of their society. With resources becoming more and more scarce, internal conflicts exacerbated and contributed to the overall decline of the Rapa Nui civilization.

Eventually, in the late 19th century, Rapa Nui was annexed by Chile. Foreign rule came with the establishment of sheep ranches and other modernity which further disrupted the traditional ways of life and contributed to the existing challenges faced by the Rapa Nui people.

All of these combined pressures led to a dramatic reduction in the population and the erosion of the Rapa Nui’s complex society and overall decline of the Rapa Nui civilization.

Micro-Empire Lessons from Rapa Nui

Manage your resources and manage them well. The Rapa Nui people are a great example of innovating and managing resources in a resource-limited environment. They delivered agricultural techniques ahead of their time like the manavai to protect their crops and enhance soil fertility. Effective resource management and innovative solutions are crucial for sustaining and scaling your business, especially in a competitive or resource-constrained market.

Play to your advantages. Rapa Nui’s geographical isolation and volcanic landscape were well utilized for natural defence and settlement planning. Village locations near the volcanic slopes provided natural protection and reduced the need for extensive man-made defences. So if you can identify and leverage your own unique advantages and natural strengths - you will also be able to enhance the sustainability of your business and create that much needed competitive edge.

This probably comes as a surprise to absolutely no-one, but resilience and adaptability are the key here. The Rapa Nui people demonstrated vast amounts of resilience and adaptability in the face of wild amounts of external pressure and held onto their cultural practices and societal structure for a long time under very challenging conditions. Similarly, building a resilient and adaptable business model is essential for enduring the eventual external shocks any business experiences and goes a long way in sustaining long term success. Flexibility and the ability to pivot in the face of any changing circumstance is a key attribute of a successful micropreneur.

Conclusion

The history of Rapa Nui offers many valuable lessons for modern micropreneurs, just like all of our previous micro empire micro dives. The principles embodied in the micro dive above - like effective resource management, leveraging unique strengths and building resilience - are essential for sustaining and eventually scaling a business in today’s competitive environment. By learning from Rapa Nui’s example, modern micropreneurs like yourself, can develop strategies that will thrive and succeed.

Before you go…

Did you know we’re on Instagram now? We’re posting insights from our previous editions and some spicy tidbits from our vast archive of premium daily editions. Head over and give us a follow if you haven’t already!

Unveiling Rapa Nui: Innovation, Strategy, and Resilience from an Ancient Micro Empire